Ah, the wine tasting experience. What could be better than a lovely afternoon touring around a gorgeous, sun drenched landscape in a tiny rental car, visiting a few wineries, nibbling on cheese and crackers and tasting your favorite beverage. Life is good, right?

For some, it’s purely relaxing entertainment – as it should be. Let’s celebrate that. For others it’s a party for the bride-to-be, or your fatcat employer. For yet others it’s a chance to learn a bit more about wines and their makers, explore the nuances of a region and build up a profile of typicity. It’s technical and it’s philosophical. All the sipping, swirling, and chit chat offer a chance to deepen your knowledge and personalize your tasting experience.

In this article we’ll focus on making your wine tasting afternoon informative and interesting. My goal at Highly Explorable is not only to inspire you to travel the world and taste wine, but to help you learn more about wine in the process! Have a lovely time and learn more about the winemaker – their philosophies and their creations.

1. Where are the grapes sourced from? Are there specific vineyard parcels?

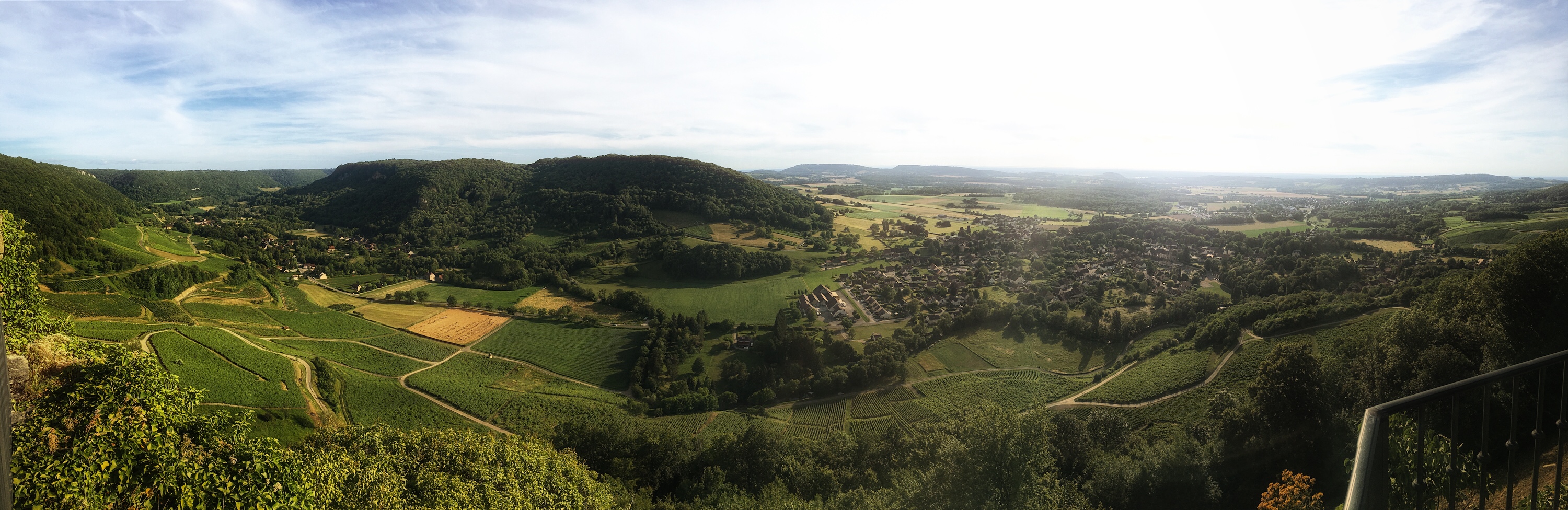

This question will tell you a lot actually! One of the key concepts in wine is the embodiment of place, starting technically with the source of the fruit. Not only is this important because the fruit is grown in local geological and climatic conditions, but because there is a culture and a story found there as well. Wine is seen to represent a location – the earth and the people who work the land and nurture the wine along. It is a product of the mosaic of conditions that start with, but is not limited to, extraordinary fruit.

Generally, most wines produced in massive industrial quantities will include grapes brought together from a broad area. Wine escalates the ladder of intrigue by sourcing from smaller areas and more specific parcels, eventually to a single vineyard. This commands a degree of value due to both economic and psychological forces. A specific vineyard, or even a specific village, gives the wine a unique identity and a sense of place, more so than will say, “California.” While enjoying your wine you will be tempted to imagine the place it came from. And if it comes from a very specific vineyard, this attaches meaning and depth to the wine – and hopefully, quality!

Follow up questions:

- Does the winery own land and manage the vines themselves, or do they purchase grapes from independent growers?

An estate winery that owns the vineyards and manages every step from the soil to the bottle will represent a more carefully crafted product, and a winemaker who is dedicated enough to be invested and committed in producing a unique wine. This means a stronger link between soil, vine, winemaker, and bottle. And a more special bottle for you!

- If a winery purchases fruit, how close is their relationship with the grower? How close are they to vineyard management to ensure quality?

They may buy fruit (even from another state if in the U.S.), for reasons of cost, convenience or availability. The time between harvest and processing towards fermentation is crucial! If they are in two completely different places, is wine really about the source of the fruit, or the winery that ferments and packages it?

2a: If the wine is a blend, what does each grape contribute?

Blending is where you will see some of the subjective artistry behind winemaking. Different grapes bring a variety of qualities to a wine, so a winemaker may blend varietals together in different proportions in order to exploit those unique qualities and achieve an optimal blend. In old world regions an appellation will have rules in place governing the grapes and general proportions, but it’s the personal as well as scientific set of judgments by the winemaker that creates their blend of the highest expression!

While it is of course true that some of the most complex and highly valued wines in the world come from a single varietal, blending can lead to complexity brought about by the inherent qualities of different varietals. Some grapes bring depth of color, some bring finesse, some bring aromas, some bring tannin, some bring spice, etc. Beyond a single varietal wine, a blend is quite literally a work of art created by the expertise of the winemaker himself.

- In Côte-Rôtie, a Syrah will exhibit qualities of earth, smoke, spice, dark fruit. By cofermenting with a small amount of Viognier (also grown in the Northern Rhone) you have the addition of floral aromas on the nose. While not technically a blend, this will enhance the Syrah and lead to a more powerful wine!

- In a classic Côte-du-Rhone blend, Grenache, Syrah, and Mourvedre each contribute similar components to the wine – fruit, spice notes, color, and tannin. Some Côte-du-Rhones will vary this blend in proportions or actual grapes depending on their style and goals. A Chateauneuf-du-Pape may be 100% Grenache, while a Saint Cosme CdR may be 100% Syrah!

- The Bordeaux blend: While mostly a blend between Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot, other grapaes may be present such as Malbec, Cabernet Franc, Petit Verdot, or even Carmenere. If you’re on the left bank, Cabernet Sauvignon will dominate the blend. Cabernet builds an overall structure of tannin and acids, while Merlot lends a silky texture and a certain finesse. On the Right Bank, Merlot will be center, flipping those roles.

Other blends around the world will be less apparent and rely more on tradition. A Valpolicella, for example, will be a blend of Corvina, Corvinone, Rondinella and Osileta. Ever had any of these on their own? Nah I didn’t think so. What does each grape bring to the bottle? Who the hell knows. But this is based on tradition, and it certainly works! While a blend such as this contributes to the overall complexity of the wine, the individual characteristics of each grape are harder to pick out, and arguably not even important.

2b: If the wine is not a blend, aka single varietal:

Ask if there are any other grapes blended in cursory amounts. Legally in most winemaking countries, even a single varietal may contain up to 25% (it really depends on the local laws, this will vary) of an additional grape and still be labeled as the predominant grape. In California for example, it is possible for a slight amount of Syrah to be added to a pinot noir for body and color.

3. Has this wine had oak aging? What kind of oak?

Oak imparts certain toasty flavors upon the wine such as caramel, coconut, smoke, vanilla, perhaps some cocoa. Oak is an integral part of the winemaking process, and is a convenient material for wine storage. Aging in oak can also smooth out some of the rough edges of youth and tame some of the young tannin compounds before bottling.

White wines will typically have less wood involved in the fermentation and maturation stages in favor of stainless steel tanks. This will preserve the clean and pure brightness of the fruit. An unoaked red will lead to brighter fruits and a wine that is fresh and lively. The addition of wood aging will introduce oak characterstics that should complement the overall style of the wine. And lead to a more complex mosaic of sensory input.

Most of the highest valued wines around the world have some oak aging. So it’s not just a preference, it’s a very real thing that contributes to the quality of the wine. Now, you can get into a very thorough lesson on the importance of oak, and different types of oak, in the winemaking process. We’ll leave that exhaustion for another day. So let this just introduce to you the a few general ideas on the subject.

Oak can be introduced during fermentation or after, when a wine is left to settle and mature. The amount of time it can spend with oak before bottling can vary from a few months up to four or five years for some Italian and Spanish red wines!

The trick for a winemaker is to introduce oak flavor without overdoing it! Wine is all about balance. If the oak components dominate, then you’re masking some of the inherent qualities of the fruit.

What kind of oak?

French oak is most evident in premium ageworthy wines. French oak is sourced from several locations around France, most famously Vosges, Alliers, and Tronçais. There are multiple varieties with different grains, in size and length of the grain. French oak is often preferred because it lends a more subtle flavor profile to the wine without being overbearing.

American oak is less in demand for wine aging, and barrels are predominantly seen in bourbon aging. American oak imparts a stronger and more noticeable profile of flavor onto the wine – notes such as toast, coconut, vanilla. If the winemaker is not careful, this can dominate. Wines that traditionally use a lot of American oak are the Riojas of Spain and the Cabernet Sauvgnons of California.

East European/Hungarian Oak is the same species as the French oak, but is growing in popularity due to it’s reduced cost. It is often used on full bodied wines, and may be a good compromise between French and American.

New or old?

New: Strong, fresh, and bold flavor influences. New oak has a lot of power in the flavor department. Try a Rioja, chances are those warm and toasty flavors came from new American oak.

Old oak offers a more subtle approach. The strong flavor qualities of new oak begin to fade after only a few years. And although the noticeable flavor components may be subdued, older oak barrels are the traditional and historical storage of choice, allowing wine to mellow nad mature. A foudre is a general term for a large storage container used widely across France in Rhone, Burgundy and Alsace for example. Wine foudres are truly enormousm, and may hold up to 12,000 litres of wine! And one of the oldest foudres can be found at Hospices de Strasbourg, dating back to 1395. (And there was still wine in it until the mid 20th century!)

Oak is very important in the winemaking proess, and adds more layers of intrigue and complexity to the story. Do not be afraid to ask if the wine has had oak aging, and why the winemaker chose that route or not!

4. What was the weather like this season? How did it affect the wine/production?

Was it typically dry? Wetter than usual? Hotter than usual?

One of the most beautiful things about wine is the idea that it is truly a product of man and nature combined. Man shepherds the process along, influencing various factors as needed, ultimately teasing out the best wine possible.

But nature controls the growth of the grapes, and that’s where it all begins. This is why wine production exists in certain regions and not others – the climate suits grape growth. What makes up this set of dependencies is mother nature – the amount of sun the vines get, and their angle towards the sunlight. The soil makeup, soil drainage, wind, daily temperature swings, and more.

Rain is obviously needed to grow the vines. Grape vines are unique in that they perform best when they struggle slightly for the water they need. But too much rain can result in too water and swelling in the grapes. If not picked at the right time, a higher water content will lead to a flatter, more diluted wine that lacks concentration and character.

So the success of a growing season and it’s resuling vintage will depend mainly on rainfall – how much and when!

5. How long can this wine age?

The topic of wine aging can be confusing to many. You may be surprised to learn that most wine is meant to be consumed within 1-3 years. A small portion of the total market is focused on wines of high value that are meant to develop and improve with some years lying down. And when would it be ready to open? Well this is speculative as well. There are some very informal guidelines in place for certain wines, regarding the number of years of aging before they are at peak expression and ready to open.

There are several factors that will inform the ageability of a wine. They are of course the four pillars! In no particular order these are tannin, acid, alcohol, and sugar.

For example, a typical bright and fruity Beaujolais is meant to be drunk young. The wine is produced, bottled, and released quickly. There is even the tradition of “Beaujolais Nouveau” which is released the third week in November from that year’s harvest (kind of a marketing thing, actually). Using the production technique of carbonic maceration, the resulting wine is lively, fresh, light, and fruity. All this youth and vigor is captured in the bottle and meant to be enjoyed.

The Four Pillars Of Wine Structure

Acid

Acid moderates the pH level in the wine, and has an important preservative role in aging wine. Some wines have a naturally greater acid content, such as Sancerre, Vouvray, and a New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc. Acid serves to counterbalance the residual sugar content, and will contribute to preserving the wine. There are six types of acid that may be present in wine: tartaric, citric, malic, lactic, succinic, and acetic.

Tannin

Tannins are a type of molecule called "polyphenols" that are naturally present in the stems, seeds and skins of the grape. Some grapes are naturally higher in tannin than others. In the taste of wine, tannins create a texture of slightly bitter group on your tongue. They act as a unifying element and preservative, and can slow the oxidation and aging process.

Alcohol

Alcohol content also acts as a preservative, but only up to a point. In non-fortified wines, alcohol is volatile, and if the alcohol level is too high, this will hasten the wines eventual conversion to vinegar. With fortified wines with alcohol levels at 17-30%, their aging potential is significant.

Sugar

Some sweet wines from Germany or Alsace, France for example, can last up to a hundred years. This is partly due to the significant presence of resideual sugar in the wine. Sugar has a complementary role to acid in terms of it’s role in acting as a stabilizer and preservative in aging wine. It’s way beyond the scope of this article to get into chemistry, but just so you know!

By contrast, a Barolo from Piedmont may take ten to fifteen years to fully evolve. By law a Barolo must age 38 months before release. This time will be spent as maturation in oak barrels as well as a year in bottle. With Barolo Riserva, you will see five years before release, 18 months in barrel. The Nebbiolo grape is naturally in high in tannins due to a higher seed count compared to other grapes. The resulting Barolo wine will have aggressive tannins and high acid, which takes time to mature. A young Barolo can be exciting for sure, and is certainly drinkable, but a few more years will likely reveal even darker secrets…

If you open it too soon, you’ll likely find a wine that is somewhat astringent and still sorting itself out. Tannins may still be gripping, flavors may seem disconnected, without mellowing into a harmonious unity. A Barolo needs that time to unwind and mellow out.

Lightning bonus round question!

How would you describe this wine, without describing the wine?

I like this question because it's challenging to answer. It touches on wine as a metaphor, not only as a food product. I leave it for last, as it can take your conversation in one of two directions. Either the winemaker or staff member will have an interesting and entertaining response that will strike whimsical, or they will go completely blank. This question is more to shift away from the technical, and dip back into the romantic notion of winemaking.

What does the wine remind you of? What images or memories come to mind, without thinking?

Is the wine ironic? Is it pretentious? Is it cabin you stumble upon in the woods? One with a warm, inviting fire?

Leave A Comment